Mahalia Jackson was seated nearby when Martin Luther King Jr. stepped up to the podium on Aug. 28, 1963, to address the 250,000 marchers who had come to Washington, D.C., to mark the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation.

King detailed the barriers that still denied African-Americans equal rights, and then he hesitated as if searching for an image to leave with the crowd and myriad others watching on television.

Jackson — the “Queen of Gospel,” as she was known — had performed earlier, just as she had at previous stops on King’s civil rights crusade.

“Tell them about the dream, Martin,” she called out. “Tell them about the dream!”

Setting aside his prepared text, King riffed on Jackson’s suggestion — repeating, over and over, the now-famous phrase, “I have a dream …”

Jackson may have heard King use it before. Either way, dreams were the continuing motif of her life. Some frustrated, others deferred. One she could scarcely believe, even when that dream came true.

The magnitude of her talent was unmistakable when she made her professional debut, in 1928, at the Pilgrim Baptist Church in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood.

“It was a voice quality no one else had,” her mentor Thomas Dorsey told the Tribune when Jackson died in 1972. “Hard to put into words what it was — a sort of cry or whine, with a lot of pathos.”

She got $4 for that initial gig and not much more for subsequent singing appearances. She worked days as a maid and laundress. Then on Oct. 4, 1950, she was booked into the veritable mecca of operatic performers.

“There I was, after all the years, on the stage of Carnegie Hall in New York,” Jackson told the Tribune, in 1955. “Think of it — me, a washwoman standing where such people as (Enrico) Caruso and Lily Pons stood. I’ve never gotten over it.”

Jackson’s childhood dreams were more modest. Born in 1911, she was raised among a dozen assorted family members in a three-room house near a Mississippi River levee in New Orleans.

Poverty ruled out store-bought toys, so she fashioned dolls of wild grass and rags wrapped around twigs. They were her first audience. “I used to sit and sing to them,” Jackson told a Tribune reporter in 1955. “I put in the sadness I heard in the men’s voices as they worked on the railroad tracks nearby, and the trains themselves.”

Her ambition was to become a nurse, but she had to leave school after the eighth grade to work as a housemaid. “Down there, you see white folks going on to school, but you don’t get to go,” she recalled.

At 16, she came to Chicago, where she lived with two aunts and dreamed of becoming a beautician. It took her a dozen years to put away enough money to go to beautician school and then open Mahalia’s Beauty Salon at 3252 S. Indiana Ave., in 1940.

Meanwhile, she’d sung in churches around the country, returning after each engagement to her day job in Chicago. “I can still iron a man’s shirt in three minutes, with not a wrinkle in it,” Jackson recalled in 1955. “You ask a good laundress about that — she’ll tell you that’s all right.”

Jackson’s lean years ended in 1948, when her recording of “Move On Up a Little Higher” sold millions of copies — eventually a reported 8 million. The song’s composer, a Memphis, Tenn., pastor, intended it to be part of one of the stately religious dramas he staged. Jackson transformed it according to the rock ’em, sock ’em approach that was her musical signature.

Her mentor Dorsey was a jazz pianist before becoming musical director at Pilgrim Baptist Church. He’d played with Ma Rainey, the great blues singer. Jackson was familiar with that style, having been introduced to Bessie Smith’s records by a cousin in New Orleans.

Those influences came together in the way Jackson belted out a song’s lyrics, punctuating them with a beat she called the “bounce.” That meant “stepping up the tempo of the music, and putting joy into the voice … sort of making a joyful noise unto the Lord, as David said,” Jackson explained to Roi Ottley, the Tribune’s Bronzeville correspondent in the 1950s.

The effect was mesmerizing, Ottley reported: “People clap and tap their feet, many fall to their knees and weep, and others pace the aisles in tears. Even sophisticated audiences, reacting to her power are lifted.”

Yet Claudia Cassidy, the Tribune’s famed arts critic, was disappointed by Jackson’s 1959 appearance at Orchestra Hall. Introducing her, the African- American poet Langston Hughes explained that Jackson didn’t sing spirituals but gospel songs. “This saddened me, as I would trade you a couple of dozen gospel songs any day of the week for one ‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,’” Cassidy noted in her review.

For her own part, Jackson insisted that she wasn’t a blues singer: “Blues are the songs of despair, but gospel songs are the songs of hope.” To illustrate the difference, she played her recording of “Gonna Walk All Over God’s Heaven” for a Tribune reporter in 1955. “Listen to that,” she said. “It’s about people who never had anything. They’re full of hope. Someday, all the toil and sadness will be gone. They’ll have shoes, and they’ll walk in heaven.”

Louis Armstrong urged Jackson to leaven her repertoire with jazz and pop tunes, but she remained faithful to gospel. When they did a duet at the 1970 Newport Jazz Festival, it was “Just a Closer Walk With Thee,” the traditional funeral march in their mutual hometown, New Orleans.

She read the Bible before going onstage and refused to appear in nightclubs where alcohol was served.

Jackson customarily closed her eyes while performing, explaining it gave her focus: “No one else is there for me — I’m singing to the Lord.”

And, of course, in front of increasingly large audiences that made her a wealthy woman. She bought a spacious ranch home in the Chatham neighborhood. In 1965, Jackson explained to a Tribune reporter why she furnished her home in the French Regency style. “Back home these white folks I worked for had furniture and I used to clean it and I used to say to myself, someday, when I grow up, ‘I’m going to have furniture like that.’”

On a European tour four years earlier, Jackson got rave notices. The Daily Express’ review of her performance at London’s Albert Hall ran under the headline: “Thousands There But Mahalia Sang To Me.” The audience at Berlin’s massive Sportpalast insisted on her taking 10 curtain calls. In Amsterdam, the applause was deafening before she’d sung a single note.

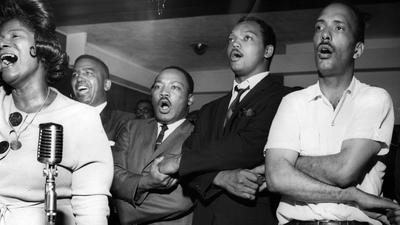

Her crowded schedule was complicated by Jackson’s commitment to the civil rights movement, starting with a benefit to fund the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott. From then on, whenever King called she was ready to join him. If he was feeling down, he’d phone and ask her to sing to him.

Her health was increasingly problematic. Exhaustion forced Jackson to cut short a 1952 European tour, and she had a heart attack in 1964.

During a 1971 European tour, Jackson suffered severe chest pains, and a U.S. military aircraft flew her to Chicago.

After being in and out of hospitals, she died on Jan. 27, 1972, in Little Company of Mary Hospital in suburban Evergreen Park. The Tribune estimated 6,000 people attended a memorial service for Jackson at McCormick Place, where Aretha Franklin was among several performers who sang. Another service was held in New Orleans, and she was entombed in Metairie, La.

The evening before her service in Louisiana, Cylestine Fletcher, Jackson’s secretary, told a Tribune reporter that, in one of her final hospital stays, Jackson told her to write down a biblical citation, which she did on a scrap of an envelope.

“You go read those verses — they’re haunting me still,” Fletcher said of Psalm 119, verses 17 and 18:

“Deal bountifully with thy servant, that I may live and keep thy word. Open thou mine eyes, that I may behold wondrous things out of thy law.”

Credit: Ron Grossman – Chicago Tribune – September 13, 2018